Separates are new cool at LFW

Payal Jain gives us nifty wearable options, Tarun dresses the groom’s extended family in dhotis-pearls, while Pankaj and Nidhi serenade mocha, and Samant Chauhan flirts with sci-fi bejewelled shoulders. By Asmita Aggarwal Shouldn’t fashion be wearable, easy, and non-fussy? If you are a believer of separates, Payal Jain has just the collection for you with a Parisian vibe! Think crochet and jute bags with flowers and crinkled skirts—she went for light embellishments, beads, tone-on-tone. If you see the history of Payal over the last 27 years, she has always had her favourites—from Chikankari which she keeps floral to Chanderi and mulmul. The natty lace collars with bell sleeves in pristine white, the indigo dyed denim shorts with coats, front knotted “happy” blouses, and her dexterous cutwork made us think about a relaxed summer. The crochet is done by hand laboriously that she used as a third element to rev up her austere offerings. The showstopper wasn’t former TV star Mandira Bedi or influencer Nitibha Kaul, but Katrauan from Banaras, delightfully airy cotton. The jumpsuits with bows tied to sleeves, came with wicker suitcase bags, triple layered strings of pearls were omnipresent, fabric flower belts, and everyone’s favourite “reader women with glasses” who love books not fleeting trends. Samant Chauhan The boy from Bhagalpur has crafted a unique journey in fashion—he serenaded the Middle East market, made a killing—this year he went all white, with hints of shimmer. He decided not to deviate from his style “long and cinched”. Gowns came with a diaphanous cape, some with one shoulder trail. His play with placement embroidery on the closure of long jackets was interesting as well as pleated gowns with starbursts. Structural detailing in exaggerated uplifted shoulders, tulle skirts worn with bejewelled bodices, he made shoulders his focus—sci fi-heavily embellished. Flapper trims on coats in charcoal black, basket weave, crinkled gowns and swinging fringes in rusts and olives. Asymmetrical flamenco skirts, tiered, peplum bejewelled corsets with riding pants made sure he has something for everyone who wants to look part of the swish set. Pankaj and Nidhi If anyone knows how to stay on the trend wagon, it’s the husband-wife duo Pankaj and Nidhi, who have built a huge business in the last 15 years. If mocha is the Pantone colour of the season, pleated capes were offered with stockings worn over stilettoes— along with appliqué, embossing and placement embroidery, three superheroes. They went for solid colours, didn’t let other hues in, mirror work and princess sleeves, added tassels and fringes, but the innovation was the sheer and polka dots mix as well as tulip dresses in slate grey. Crochet is climbing the fashion firmament like a tall vine, as organza capes accompanied roomy pants. Bejewelled bustiers, cutwork extensively used, shoulders upturned and stiff, in this mix was lithe 90s model Sapna Kumar always fabulous. Tasva: Tarun Tahiliani The dhotis and jackets in tone-on-tone, one never really tires of it, especially in menswear, but what stood out in this show is the older, real model coming of age, he may not conform to society’s standard may be small and stout, but he is reclaiming his right to the catwalk. Mogras on the wrists as well as men in shawls woven Tanchoi and Banarasi, some with the disappearing moustaches, the Patiala salwars, chokers found soulmates in sunglasses. The waistcoats came with functional pockets in mints and blush pinks, as white-haired men above 70 are maybe Tarun’s new customers. Happy to see Kolhapuris and Chef Ranveer Brar in a sherwani, just like the following female model in one too, making it unisex. Live tabla and guitars, dhols, a marriage procession, the largest conglomeration of male models, just like the song played in the background by the former Spice Girl-Geri Halliwell it was literally “Raining men”. Velvet sherwanis, creams met coffee hues, as pleated dupattas with sherwanis and pearls swirling was ideal for the groom’s extended family dressing.

Pondicherry, French, silk velvet printing

Craft-soaked Bandhini to experiments with Chikankari, Naushad Ali adds a European influence to Indian textiles serenading a global buyer. By Asmita Aggarwal His father is a textile merchant, based in Pondicherry, so Naushad Ali grew up surrounded by fabrics from Bengal to Orissa, he would sit on the bundle and watch TV as a young boy. His interest grew to study fine arts, and cleared NIFT Chennai, where he studied textile design. “Auroville had a huge influence on me—specially its multi-cultural approach. The predominant French influence, people from different nationalities co-existing teaches you how the world has no boundaries. When I began my brand, I knew it had to be global,” he adds. He believes there is a lot of misconception around textiles, it is only restricted to Indian wear, but you can channel French elegance with a kurta. “A lot of my friends shut down businesses in Covid, it is an interesting and challenging time, every day I see new brands on Insta, who will survive only time will tell,” says Naushad. Celebrating ten years of his brand, the NEXA spotlight winner, believes his USP is showcasing textiles in a refreshing way, just like the poster on his office wall, “Why should sustainability be boring?” He keeps researching, when he takes up a craft, admits, “when you buy from us, you know its depth, like our Chikankari, we have introduced it with a stronger identity, used in a contemporary way. Just like Bandini and indigo, two of our signatures with a distinct European influence,” he explains. The play is in the motifs rather than the conventional paisley; it is more global in its appeal and demeanour. “We live in one world due to Insta, but I maintain the dignity of the technique I work with, though the result is a cocktail with my interesting ingredients. I fear monotony, each piece must not be repetitive,” he says. His experiments with silk velvet printing, maintaining the consistency of the ink, became his bestseller. “I am a Tamilian, grew up in the South, if you observe Indian women, while shopping at Nalli, they know their saris, quality of gold, and are aware of what they are paying for. Same with Bengal, women value crafts, and culture. After all, fashion is a desirable product, it must 100 pc look good,” he explains. LFW X FDCI 2025 he is focusing on yarn dyed indigo, denims hand woven in Bengal, South Indian checks from Madurai, without abandoning his USP Jamdani. “Now I see a uniformity in dressing, everyone looks the same, but a white shirt can look different depending on the personality of the wearer, and most importantly region-South to North,” he confesses, adding people used to dress for themselves in the past, now that spirit is lost somewhere with social media onslaught. Interestingly, he talks of the rising culture of thrifting, like the jacket he made for his Pondichéry based French client Vincent. His son wore it 10 year later and sent him a picture, the key is trendless clothing, it may lie in your cupboard, but is never obsolete. “We wanted to open with contemporary freestyle dance to establish a connection with the clothing, channeling the spirit of exchange of garments act on the ramp. We all love dressing each other, there is joy in it,” he explains about his presentation. Does one need money to survive in fashion? He has an engaging hypothesis—you can be privileged to inherit dad’s burgeoning business, but have zero design sensibility. “Creativity and commerce must co-exist,” he reiterates, adding, “I like to address the feminine side in menswear, embroidered silk shirts, gender fluid, simple tailoring, spotlight on fits. The future is responsible fashion, that withstands the test of time,” he concludes.

Luck by Design

Somaiya Kala Vidya, is creating a space for artisans from Gujarat working with Bandhani, Ajrakh, block printing to applique, equipping them with skills that combine—marketability with design prowess-craft is just not art. By Asmita Aggarwal You would never expect a chemical engineer from the acclaimed NIT, Trichy to be working in the development sector, but there is a lot more to Nishit Sangomla than just his degree. He won the SBI Youth for India fellowship which took him to the Barefoot College, Rajasthan, established by visionary Bunker Roy in 1972, hoping to empower rural communities. In “Solar Mama”, how to fabricate solar panels, lights and photovoltaic circuits is taught 110 km from Jaipur, Tilonia village. Nishit began working with them, and it changed his life forever. He had found his true calling many years ago. Though he did notice it was dominated by women, as the men had gone to bigger cities to work in mines, never sent money home, forcing them to fend for themselves. Agriculture was not an option—but the region was loaded with crafts—they worked with leather, made durries, everything was laboriously hand-crafted—a gem waiting to be showcased to the world. “They are skilled, but did not know the technical aspects—marketing to supply chain management. After all, erstwhile kings wore crafts that are now museum pieces, all they needed was design direction,” says Nishit. This gave birth to the design lab they set up, to dig deeper into concepts, educate artisans, the seed of the idea came when Nishit met the legendary Judy Frater, an anthropologist from US, who came to Kutch, Gujarat in the 70s, the rest is history.. Judy, lived 30 years here, with artisans, particularly women embroiderers, studied their traditional crafts, Kala Raksha Trust she set up in 1993, to empower artisans. After the 2001 earthquake, she founded the Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya School in Meghpar, Anjar, Gujarat, the first design school for traditional skilled artisans. Bonus: they are setting up a natural dyeing research lab, which anyone can use. When he met Judy in 2016, she mentored Nishit, in 2019 she wanted to go back home, Nishit took over as the vision was clear. Bandhini, Shibori, Batik, weaving, block printing, patchwork to applique—artisans are taught how to modernise and sell. There were many hurdles he faced —in the one-year program, women artisans’ families were not comfortable to send them to a residency (12 women, 12 men trained every year, number varies). Interestingly, the age is dropping for students, earlier it was above 30, now younger artisans are joining, who had given up this generational skill. There are six modules— they can learn from street markets, retail stores, and exhibitions—colour development to trend forecast, experimenting with motifs, each skilled artisan is taught various verticals to enable him to be market ready. “When we take interesting calls like increasing dips in indigo the results are spectacular—innovation is the game,” he smiles, adding they also added violet to Ajrakh giving it a new spin. At LFW X FDCI Somaiya Kala Vidya showcased Ajrakh by Ziad Khatri, Alaicha (Mashru) by Amruta Vankar, ‘Anatomy’ by Mubbasirah Khatri, ‘Mystery’ by Muskan Khatri, ‘Tradition to modern’ by Shakil Ahmed, the school has now been taken over by Somaiya Trust, which is a prestigious educational institution based out of Maharashtra since 1942. Amrita Somaiya, who owns the school, has a Bachelor’s degree in Economics from Simmons College, Boston, and her husband did Chemical Engineering from Cornell University, a Master’s degree in Public Administration from Harvard University. Their family originally belongs to Kutch, Karamshi Jethabhai Somaiya, was an Indian educationist, who founded educational institutes in Maharashtra, was awarded the Padma Bhushan, Samir his son is carrying forward his legacy. “My father-in-law worked relentlessly after the earthquake to build Kutch, then my husband met Judy, as she was looking for opportunities to continue the craft work,” says Amrita. Amrita’s father is an architect, mother an interior designer, she inherited the love for aesthetics from them, crafts has been her mainstay, thus subsidised education for artisans at Somaiya Kala Vidya. “Real craft is handmade, each artisan who showcased had a personal story in the collection, like Shakeel bhai and the beautiful Batiks, it was contemporary, but soaked in craft,” she adds. An avid lover of textiles, from Ajrakh to Bandhini, hand woven is her go to, she spends time in clusters, and from grassroots understands how to bring awareness to the processes. Juhi Lakhwani, business development officer at Somaiya Kala Vidya, joined this year, but her experience is vast—she won the Naropa Fellowship, which took her to Ladakh. She worked with traditional artisans in carpet weaving, realised handicrafts are losing their identity, and wanted to teach them social entrepreneurship. “The products worked well, but Covid hit, we had to pause. The key was teaching them e-commerce, digital merchandising, it worked in their favour,” Juhi says. At Somaiya she helps them market their products, with design intervention—Soof, Rabari embroideries are much loved along with Batik. Somaiya Kal Vidya has opened another school in Karnataka, Bagalkot; they have a store in Prag Mahal in Bhuj. “The reason why Gen Z does not buy craft is the lack of awareness, they have been brainwashed by Westernisation. Artisans have saris and stoles, and silhouettes need to be taught to serenade a younger clientele,” Juhi adds. When you see artisans like Mubbasirah combine traditional Ajrakh blocks with hand painting, or Amruta’s new developments for Mashru, you know they are set to succeed. Alaicha translates to Mashru in Kutchi, it is associated with the Ahir community, each pattern reflects legacy —they have a new palette, in some ways redefined it. Mubassirah is the first female artisan to step into the male dominated Khatri Ajrakh artisans rejigging it with freehand painting! Craft is business now, not just art. “I began learning from my father six years ago after he returned from SKV, I’m the only woman in three generations from Ajrakhpur to take this up,” says Mubbasirah. Ajrakh means “leave it for a while” in Kutchi, it takes

Clothes with feelings

From serenading poets to artists, Rina Singh’s Eka is a case study of craft upliftment. By Asmita Aggarwal If clothes could have feelings Eka would be a right fit! Rina Singh, who built a brand, brick by brick, over 13 years believes it took years of developing product knowledge and working closely with clusters and weavers that helped her finally launch a brand. Unlike Gen Z who know marketing, but learn about product excellence along the way, their skills are so polished that business turns out to be good! “They do it right out of college, I took several years to have the courage and wherewithal to launch my label,” says Rina, adding, “the world of design has changed unequivocally.” Eka and Eka Core are two different ethos—but same mothership, the latter is ready-to-wear, younger, less moody, uses archival textiles and repurposes, so circular in ethos. Rina overdyes it, uses quilting, makes it trans-seasonal as most are leftover fabrics. Eka is known for its love for hand spun and slow, thus the making process is not instant and takes a year of planning. She took a concerted decision to be on the ramp, after a hiatus, to offer woven wonders from Bhagalpur, Banaras, Kota to Bengal, telling a story in Muslin, lace, inspired by Amer, Jaipur with its imposing mirror mosaics, for LFW this year, but she has interpreted it differently—appliqué to tiny embroidered motifs. The idea was to have movement in clothing, like choreography, how clothes adapt to the body and its wearer; as the DNA of the label remains the same every year, but the inspirations are rooted in craft upliftment. You may have boxy trousers, laces only show shifts in moods, things you can wear from Kutch to Tokyo, as it remains feminine, layered, and translucent—this time it’s silks, gossamer and diaphanous. “Sandeep my husband, is a pillar of support—he manages operations, so I am free to design, it takes a huge load off me, in the last decade, he has been a backbone. But I have learnt marketing needs to be loud, brands must have their own voice, and over the years I have learnt not to be rigid about my product,” she adds. Kurukshetra where she was born to agriculturalists, made a deep impact on her psyche growing up, she valued crafts and the “thinking before doing” process of clothing, where you deliberate rather than buy –it is laborious, time consuming, and expensive, but it is also timeless and hand spun, the beauty is unmatched. “I come from a Rajput family where traditionally women invest in weaves, pearls and Kashida, as well as vintage shawls, they understand aesthetics,” she says. Working with the European markets, especially Japan, Rina believes the real jewel in the crown in India is ready to wear, yet we are focussed on weddings, a money churner. “I know the Indian woman likes to be comfortable, yet classy, so why not give her craft-soaked offerings with hints of colour?” she concludes.

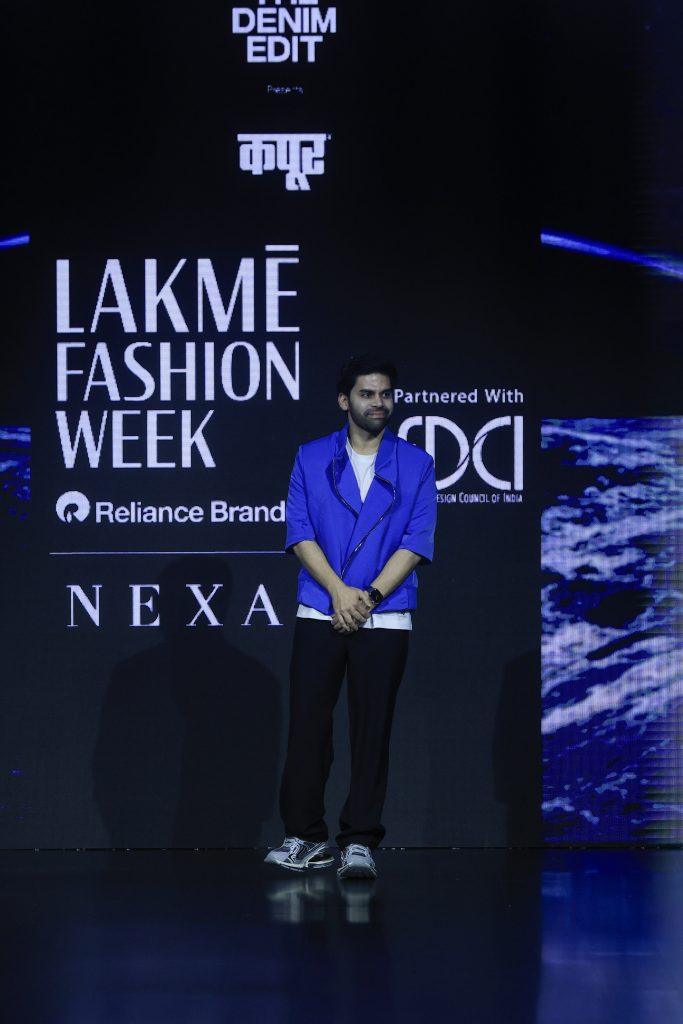

80% feeling, 20% aesthetic sells a garment: Dhruv Kapoor

Dhruv Kapoor brings his PSS (print, surface and silhouette) tastes to the Denim Edit by FDCI, at LFW as he handpaints, laminates, embroiders the versatile fabric. By Asmita Aggarwal He is a regular at Milan Fashion Week, and his 10-year-old brand, was nominated earlier for the International Woolmark Prize, but Dhruv Kapoor is undoubtedly a favourite among the swish set. His hybrid blazers, balloon vests, Indian Devanagari bold type phases for branding, t shirts that announce “I dreamt we spoke again” or “We were lovers in the past life”, he also handcrafts leather, mixes it with crochet to create totes. Kapoor denim sometimes comes with little teddies embroidered sitting quietly probably waiting to be picked up, or his interstellar shirts, cargo jeans, stamped hoodies, the whole perspective is young and almost irreverent. While in Milan he worked with Etro, where the family-owned business of the Italian label Gerolamo Etro introduced the paisley pattern—various forms and hues and their variations, it is the house’s signature design. Maybe from here he found his love for Gilets—though Kapoor does them in his own ways—sometimes in denims with a lot of zippers included for a futuristic feel. His forte remains denim, handcrafted, and if you look closely there is toy flower jackets, hand beaded, 3 D detailing and this also won him the Vogue India Fashion Fund in 2015. The Istituto Marangoni and NIFT Delhi educated designer, says, “Denim has been one of the brand staples since the beginning. We enjoy exploring diverse options that would help us enhance or uplift its appearance or natural properties. Denim seamlessly fits in every season,” he says. If you go through his e-commerce site it has three categories—man, woman and unisex and most photoshoots are done with models wearing oversized glasses— he seems to have a kind of obsession for them! And interestingly the bags are named “Seeker” almost Rs 50,000 seems tough to be sought! Participating at the FDCI Denim Edit, for the FDCIX LFW he has fused multiple formats in diverse configurations — raw, laminated, washed, embroidered, or painted. Interestingly each version performs differently. His aim is always to minimize waste and adopt circular practices. The design process would ideally meld old and discarded with new and innovative. “We annually release an upcycled collection that is built from leftover scrap and discarded items across multiple categories,” he admits. Kapoor signature has been printing, silhouette and surface, over the last decade, he has mastered the approach and perfected the details inside and out. However, it is essential to keep evolving season after season by learning from the previous seasons. “We are always exploring, adopting new technologies and techniques to update our process,” he explains. “What I read and the mix of cultures that I grew up in- always influences our design process. Literature addresses ancient legends or science from the Vedas, even some protopian fantasies. It is always a combination of diverse cultures through a blend of information coming from multiple eras blended to make them more relatable to the current system,” he explains about his love for books. With designers making a foray into the international markets through Paris and Milan fashion weeks, Dhruv believes the latter has been an exciting part of both the brand and his personal journey. He admits one always learns from the environment that surrounds us, Milan boasts a healthy and forward one, especially in the field of fashion, design and lifestyle. “From my understanding- the consumer is the same globally. It is 80% of the feeling and emotion a garment would generate and 20% of the aesthetic. We give in to how it would make us feel over simply how it looks. The only thing that changes is the climate and cultural impact of that region on the consumer choices- which are easy to implement and modify one product into multiple versions. But overall, they are all the same- they want the same things and all they want is to feel good,” he confesses. Denim remains such an enduring staple in every one’s wardrobe, Dhruv attributes this to its versatility that helps you blend two polar worlds of formality and everyday wear. Anything denim would always last long and work round the year. “I personally enjoy all versions of denim, my favourite a total denim looks in a sober enzyme wash,” he adds. There are no weaknesses or challenges but all learnings, in life. “My biggest learning personally and professionally is being patient- especially between two seasons and to let the creative process pass through the creative blocks peacefully, by diverting our attention into fine tuning the process during that time rather than getting frustrated. My strength is my team- their commitment, loyalty, and the countless hours they put into the brand is something I am very grateful for,” he concludes.

Blue blooded fit by Countrymade

Every setback in life kind of teaches us, for Sushant it was his brother’s sudden demise, he used the pain to pay homage to his memory keeping it alive each year. At the FDCI Denim Edit he gives the resilience of denim an interesting twist with hand painted leather. By Asmita Aggarwal It was a happy surprise to be part of the FDCI Denim Edit for Sushant Abrol, Countrymade, and a perfect fit as 50 per cent of his collection for a recent Paris trade show was crafted out of this sturdy material. “Trail Dust” conjures images of a dust cloud you leave behind, while driving on rugged terrain, it seemed to be in sync with what Abrol has been doing for the last five years-a sort of continuation. Thus, the dust cloud is an analogy of the essence of our journey, a bit like how with our travels we bring back memories. Denim for the show has been captured in its rawness, as it exudes resilience, much like the sole of shoes we wear, which get worn out, or our jeans which wrinkle over time, the fabric folds, crumples, these are the effects given by Abrol to show the veracity of time. “We don’t embroider tigers or leopards, or sequin birds, thus crumpling is our embroidery,” he smiles, adding, “lines play a very crucial role in denim—cracked, folds, we have worked with selvage denim, 100 percent cotton, we do not use stretch. Denim is inherently strong, and can play with many techniques, experiment, unlike something like Chanderi which may tear if put under pressure-as it’s delicate.” The label started as an homage to his older brother who passed away in 2019- Squadron Leader Samir Abrol died during a training sortie in a fighter jet crash. Abrol studied from NIFT, Mohali, in 2010, he wanted to join the armed forces passed the entrance for the Service Selection Board (SSB) but was not selected after the group discussion. His brother wanted him to start his own label, he was a class topper, but his life was cut short. The label never forgets him—somewhere Abrol keeps his aura alive. Though he is not showcasing it, he has a line of denim ecru, unwashed, with patchwork, camouflaging, applique, his signature looks along with frayed denim, in tandem with his military inspirations, a signature. The fraying for him depicts the journey of the “aged soldier” coming back from war brimming with experiences—the hues rang from black, indigo, and navy, screen prints of dust particles, splattered, bullion knots stitched unevenly-it was a show that brought out the concept together beautifully. “In menswear structure gives confidence, we add artisanal techniques, to make it interesting, but denim is no longer casual. We have constructed blazers, almost making it semi-formal, you can wear it for an intimate evening out,” he confirms. This season he has Safari suits, vests with leather accents, hand painted leather, which has already been picked up by stores in the Netherlands and Beverly Hills, US. The beauty of a Countrymade show is its music—which is written by Abrol himself, this time inspired by an Irish pub song, titled “Rocky Road to Dublin” by the High Kings. It became an anthem for workers who after a hard day’s work unwind singing about their day. Writing poetry, he has added all his collections names till now, almost ten, (Homecoming, Band of Brothers, No Man’s Land et al) in the song and composed it in the Irish lyrical style. “The idea is to enjoy the moment, also celebrating the perseverance of not giving up, to come up every six months with collections,” he concludes.

Batik has unique monotones: Madhumita

Working with Batik master craftsman Shakil Khatri for the last ten years in Gujarat, to revive the 1000-year-old tradition using vegetable dyes, Madhumita Nath of Ek Katha hopes to serenade a young audience with reimagined crafts. By Asmita Aggarwal She studied textiles at NIFT Mumbai and JJ School of Art, the Mumbai-raised, Nagpur-born Madhumita Nath of the label Ek Katha took time to launch her label. She came from a renowned family of science mavericks, with her grandfather Prof. M. C. Nath, moving from Dhaka to India, setting up the Biochemistry institute, in 1946, Nagpur. Most family members are Ph.Ds, so when she decided to study textiles, it was met with “surprise.” 2016, was the year when she decided she would like to concentrate on Kutch weavers, she sought advice from mentor Kudeep Gadwi, who took her to meet artisans exposing her to lesser-known jewels like Batik from Mundra, Gujarat. The “khakan” is made locally, earlier they used oil of a seed, not paraffin wax to dye, but now only four families are left out of hundreds who have abandoned this process, six in the adjoining village— digital printing killed traditional art. “You can make digitals in Rs 15 to Rs 30 per meter, which ends up in Dadar market, it is quick. Ancient techniques, 1,000 years old, have a subtle layering, the beauty of it has been erased due to bulk digital prints. Batik used vegetable dyes, chemical- free, laborious, painstaking but excellent,” says Madhumita. Master craftsman Shakil Khatri’s family has been batik block printing for six generations, using oil of the pilu tree (Salvadora persica), locally known as kakhan, as a resist. As it is thick and sensitive to heat—the oil can only be used in the morning. Kutch batik left natural dyes shifted to naphthol-based ones, but Shakil sticks to sustainable processes, he makes 12 shades of natural colours from indigo, rust iron, turmeric, pomegranate skin, madder and onion after he was trained at the Kala Raksha, in innovative ways. He gave life to Batik with new designs, artisans in Batik Kutch are Khatris, Kutchi-speaking Muslims. “Khatri didn’t give up block making, his gradations due to the layering is unmatched,” says Nath, who in 2018, made a line for the Sustainable fashion day in Spain with The Circular Project. “I am not a businesswoman, when Covid struck, I shut shop for two years,” she says. Providence gave her an amazing opportunity to learn from an incubator program for women entrepreneurs, NSRCEL, started by the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore, in 2023. IIM (Bangalore) has partnered with Goldman Sachs, Capgemini and Maruti also. “I received helpful inputs on the financial aspects of running a business, for six months through the management institute. It was a learning to see where I belong, how to survive when you do slow fashion, meet investors, pitch in front of them,” she adds. Apparel Export Promotion Council (AEPC) membership helped her figure out how small batches of hand-made can be exported to the US and the Middle-East. “I wanted to do something craft-based, but I am not a sustainability warrior,” she admits, as she worked with kala cotton, reducing carbon footprints with hand-made techniques. “I love crafts, bazaars, haats, seeing lots of stuff stacked up, and the beauty of Batik is that it is monotone, unique in so many wonderful ways,” she adds. Generally, she admits, Gujarat is often associated with colourful embroidery. “I did start with Ajrakh, but soon shifted to Batik, Kala cotton is not glamorous, but I know North Indians will be hesitant, but the Japanese will buy it at any price, as they know its value. When you can get a heavily embroidered piece for Rs 10,000 anywhere, why would anyone but pure, natural, plain fabrics? Many don’t realise the artistry,” she confesses. For LFWXFDCI, Nath has combined Batik with fabric cording, using khadi and kala cotton from Bengal, also paying homage to Kota Doria, adding delicate, subtle textures to create flowy shapes. Her love for patchwork, cutwork and quilting used in abundance can be seen, without serenading waist defining silhouettes, yet the line is young in appeal. “I would like to do B2B exports in the future —I know I have to build my capacity first,” she concludes.

CDC winner’s clothes with a conscience

Life took a turn for the better from seeing his grandfather’s dyeing unit polluting, to now only dealing with second hand garments, reconstructing them into new shapes, Ritwik Khanna, 25, of Rkive City is a force to reckon with. By Asmita Aggarwal This generation is something else—they really know what they want to do, and one thing is certain, they want to work for themselves. Thus, talking to the Amritsar-born Ritwik Khanna of Rkive City, only 25, was refreshing. He won the Circular Design Challenge in partnership with the United Nations and Rs 15 lakhs fund at the LFW x FDCI show His grandfather had a textile mill, the dyeing house, he noticed, no one ever really cared about the environment, the water was contaminated due to the chemicals dumped in it. At that time, he was not aware of its toxicity, it was not treated. The business shut down, his parents began weaving cashmere scarves, his earliest memory is of sitting on the shop floor packaging, as there were not enough employees for an SOS order. His mom used to run a children’s boutique, often dressed Ritwik in boys’ and girls’ clothes to show customers how it would look on their kids, his trips to Sadar Bazar to buy material were a lesson. As serendipity would have it —life took a 360 degree turn when he left to study fashion business management at FIT, New York. Though Mayo School, had exposed him to seven different types of uniforms he would change in a day to keep up with the strict regimen —in a way it was universalizing design. “Whatever I had grown up seeing, New York was different. I remember having a conversation with my roomie about fashion, when he suddenly stopped, and started talking to a random stranger on the road about his Supreme t-shirt. He knew the price, which year it was launched, graphics, its entire history. This took me by surprise, it was not my culture,” he laughs. He giggles and reveals his fashion was “USPA chinos”. At FIT everyone looked “cool”, they really dressed the part, and trying to keep up, all Khanna could afford was second-hand designer jeans. “In India we don’t like wearing ‘worn before’ stuff, in America it’s a classic trend. I saw the quality was good and began running a small business,” he shares. He would flip Comme des Garcons, Rick Owens second-hand stuff he would buy for almost nothing, and make a 300 percent profit selling it on eBay. He began rolling in moolah, accidently, he did not need the business degree he was already adept at. But he did come back, without completing his course. Covid hit, and education through a computer did not make sense, spending US $25,000. On his return, he visited second hand clothes collection centres in Panipat and Kandla Gujarat, and wondered what happens to torn, damaged clothes, discarded clothes—they are shipped to India. Panipat is known as the world’s “cast off capital”, tonnes of clothes come from UK, US, and other countries, from the port town of Kandla, Gujarat they are popularly known as “mutilated” clothing. Ritwik was alarmed at the kind of “stink that emerges from the factories”. “Only ten per cent of this is recycled, I decided to work with discarded waste, consumer textile, we were able to use old garments, and create something brand new,” he says. Though he does admit unlike in fashion where you get to choose the finest silks and dupions here you work with limitations, as there is no roll of fabric, or colours or any frills–just your imagination. He is happy in the last 22 months he has managed to make a small impact on the environment. His label questions existing supply chains, he is remanufacturing garments, he sorts out the garments at his factory—white shirts, camouflage, old jeans, then the processes begin—sanitising, reconstructing, it is an end-to-end solution, as a brand. “The hardest thing in garment upcycling is consistency, each piece is different, now two pieces are alike,” he says, adding, he elevates the androgynous ensembles with touches of hand embroidery, patchwork, applique, his power lies in the way he crafts them; they do not seem upcycled– he lets the natural fading persist. His brother, 21, has joined his business, he is the operations manager, a “Genius”, he calls him, both sons now don’t work with family business, and they hope to progress, even though they are bootstrapped. He says one day his dad will be proud of the work he is doing. “I know my North star, I know who I want to be,” he smiles, adding he is not a sustainability activist, and neither is he interested in putting anyone else down, to show what “good work is” but he is certainly in a league of his own. Why Rkive City because he will one day have a city that understands how important upcycling and recycling is, also why RKive as it is archival fashion that he is serenading—perfect moniker!

Ujjawal’s 10th with homage to “self”

Antar-Agni as the name suggests is a journey within—thus his unisex label is a lot more than just layering, drapes and lapels, it is an exploration of the meaning of luxury, and why its connotations change to cater to an individualistic mind. By Asmita Aggarwal Some things in life are meant to happen, it is called serendipity—that’s why when a doctor’s son went to a small shop in Gorakhpur to get NIFT entrance form for his older brother, he could never imagine, he would one day be a textile graduate from the famed institute in Kolkata. Ujjawal Dubey’s Antar-Agni today completes 10 years, for an underconfident, somewhat hesitant boy from a small town, who had no exposure to fashion, to building an empire, winning a spot on the Forbes Under 30 list, it is no mean feat. Dubey’s questions about life and its vagaries have often led him to the right path, whenever he felt despondent and out Bhagvad Gita came to rescue. During covid too, when businesses were shutting down at the speed of lightning—one quote kind of saved the day –”Only those who are calm in success and failure can win the battle of life.” He loves literature, never attempting to deep dive into it, rather his motto has been spirituality, understanding human nature, and its fallacies as well as the desire to protect one’s image. Image is everything now, thus he came up with the exploration of duality in it—you pray but in business don’t think twice before cheating someone for money. “Two-faced” seems an appropriate name for his LFW 2024 line in collaboration with FDCI, a collection divided into three parts—Gyana, Vairagya, Bhakti. If you observe his journey closely, women buy his unisex ensembles—baggy, bigger shoulders, draped, layered—those who are “cooler in terms of styling and self.” He is unabashed when he says the biggest take away from this decade-long sojourn has been the “strength of common sense and truthfulness towards your inner being”. Architecture has always moved him, and so has geometry, thus when he was looking at temple-carved pillars made thousands of years ago, he was fascinated by 3-D imprints. It was the genesis of abstract prints/embroideries. The question this year is “Are we really righteous or is it a pretense for the world?” As a child Ujjawal wanted to be an orator admired the skills of Amitabh Bachchan, he believes, all languages matter not just the ones related to the body. Only if we didn’t live in such a structured world, creativity would be everywhere. Gyaan in his line is represented through Western cuts, structure, lapels, 3-piece suits, and jacket lengths. While Vairagya is depicted through layering, and Bhakti is where you devote yourself completely, thus exaggeration, blacks, deep purples, and greys, as well as forest greens. You can see suspenders, detailing with faux leather, belts, hats, all constructed with his vision. Human mind is searching for security, fear drives us to look for eternity, longevity, but covid gave him “liberation” as he thought “how much worse can it get?” When he started, in 2014, there wasn’t even one rack in big showrooms for menswear, he never had a template he could follow, he thought of how he would survive. And in six months, he realized what an uphill task this is— “How do we sell?” He admits he is getting better at handling stress, and thanks to spending time in nature at his Noida office, where he has let in a piece of sunshine, greenery into his living space. “I was listening to a Youtube video by Andre Taylor, giant in luxury entrepreneurship, he said something that gave me perspective. How do you define luxe? It starts within you, it is the tiny things that give you joy, how you look at yourself, luxe is not a bag, that’s too narrow a definition,” says Ujjawal. Not a big fan of embroidery, as it “speaks too much” he uses it in moderation, like zari this year, cutwork, appliques, and jacquards he developed in Banaras, or his handlooms in Meerut that were woven by carpet weavers. If you ask him why he loves everything natural, it comes from watching his maternal grandfather dress only in Khadi. He used to be a Gandhian, so the Nehru cap, dhoti (even in winters), and waistcoat was his uniform, his friends dressed the same way too. “It was in mélange grey, everything was monotone, even the socks, but looked extremely interesting,” he smiles. His family gave him complete freedom to do what he wants, and even though he says he is “ambitionless”, he has achieved by just moving on without a road map. “Dressing is a mood, everyday it changes, clothing is just one part of it,” he concludes.

Arundhati Roy, Mira Nair, Kiran Rao and me share common artistic goals: Aneeth Arora

From little hearts floating on smocked dresses, Hello Kitty nostalgia, to intensive embroidery details, as well as design interventions on textiles, Aneeth Arora celebrates 15 years of Pero with a FDCI show at LFW. It has been a long road from Udaipur to creating a million-dollar business for this craft crusader. By Asmita Aggarwal Udaipur is a quiet town, very underexposed, living in a microcosm, but Aneeth Arora’s mom wore Garden saris, and Babita (the erstwhile Bollywood actress, better known as Kareena Kapoor’s mom) inspired kurtas and churidar sets, she loved fashion. She stitched clothes for a young Aneeth, from leftover fabrics from her grandfather’s kurtas—replete with cartoons, laces, patches, and flowers. “I do not know how she had children’s catalogues, Korean looking kids in them. In my friend’s circle when I went down to play in a middle-class housing society, in the evening, my dresses were admired. ‘The girls would say ‘look what Aneeth is wearing today’. My mom was quick too so every week I had a new one on,” says Aneeth, who opened the LFWXFDCI 2024 at 13 Barakhamba Road, in the capital. Entire building resembled a child’s birthday party! Thus, “nostalgia” plays a huge role in all her collections, this year is special, she celebrates 15 years of her brand, it is the core of her ideology. “There is a seriousness when we work with textiles, I thought there must be a lightness when we present it to the world,” she smiles. When her sojourn began, very few buyers understood textiles, there was no dearth of craft, but it did need refinement. Either they would starch the Jamdani too much or the wool was too coarse making the wearer extremely uncomfortable. Intervention must be from the yarn stage, is what she learnt at NID, Ahmedabad, also garments must feel good against the skin—like her Kullu Pattus, soft merino wool, refined, and it has been wholeheartedly embraced, the dyes used to bleed now they do not. When you see a Pero outfit, you will always notice little hearts floating around, somewhere there is romance, even though when she started, she was not sure if the buyer would like it, she would hide them in folds. It was her way of giving love to them through embroidered hearts, later this became one of her many intimate signatures. After two years Pero’s show is back, it is much anticipated, as she works with handloom, she wants nothing to be rushed—woven textures take time to execute. Pero shows whether it is a pajama party, or “Cuckoo and Co.”, with mad hatters or “Alice in Wonderland” are a treat for the audience, and what she is successfully able to do, is present textiles minus the rigidity, rather than being academic about techniques she makes it fun. “I learnt this from my mom, she would teach me through stories, she would sing ‘State and capital’ to me and I know it till today. I could never mug up or memorise, but storytelling always worked,” she grins, maybe that’s why you see models dancing, as confetti burst on the runway, it is part of her expression of style, transporting you into the world of a child, where she creates her own universe. In her press kits there is always a piece of Pero, once a year she shares her joy of crafting a collection, and like Coco Chanel she loves the flower Camellia, maybe because it represents resilience unlike other delicate ones, it can withstand harsh winters. “I like it, as it is underrated, the rose is considered the king, but I call camellia a modest rose,” she adds, even though Aneeth can never be seen donning florals, she is more of a Baby Breath or Forget-Me-Nots, the little blue flowers, kind of person. Unlike Rahul Mishra, or even Gaurav Gupta who in their own ways are marketing crafts to a global audience through Paris Fashion Week, Aneeth does trade shows, if given an opportunity she would love to. “Globally they don’t know our story, only our product,” she admits, Pero is available in 350 stores worldwide in 35 countries. Few know her fans extend beyond the swish set—she has ace photographer Dayanita Singh who comes and shares her latest projects, Booker prize winner Arundhati Roy works in her Patparganj studio known for the bright red letterbox standing outside like a modern-day mural, Mira Nair the famed filmmaker is a diehard Pero fan. “I am not much of a reader but I love pictures, I am a book collector and I have everything from art to architecture, we have always attracted alternate artists, like-minded individuals, filmmaker Kiran Rao whose film Laapataa Ladies is India’s entry for the Oscars. There is an honest relationship with them, pure appreciation from both sides,” she adds. Even as the world is corporatizing and fashion brands have been taken over by ABFRL and Reliance brands, Aneeth like Yohji Yamamoto or Issey Miyake does not want to sell her business—she wants to be small but impactful. She never invested in a huge retail space. “I do believe there is a right time for things to happen, the universe is a big planner, I want to create a space where I can tell my own story,” she admits. This LFW she is paying homage to the culture of DIY, GenZ loves making their own clothes. She has indulged in old textiles cutting them up and making new ones -patchwork—maybe it is grandma core but she has elevated it with French knots and crochet. There are beautiful Calcutta bedsheets in white poplin with red embroidery that have been converted into easy dresses. It also resembles Hungarian table cloth Aneeth saw, and loved the austere lines. Her constants have been Mashru and Patan checks, Chanderi and Maheshwar done in a DIY way, she mixed fabric together. But what about those who cannot afford a Rs 50,000 Pero dress? Some years back she had a capsule line titled “Lazy Pero” where embroideries were less,